End-to-end website testing with Playwright

July 20, 2022 / 26 min read / 9,015 , 3 , 0

Last updated: February 01, 2023

Tags: testing, pytest, python, web, playwright

We all know testing our code is important, right? Automated tests can give peace of mind that our code is working as expected and that it continues to work as expected, even as it is refactored. Python has the pytest framework that offers great tools for testing our backend python code. You can check out my blog post, 9 pytest tips and tricks to take your tests to the next level, to get yourself jump-started testing in python. And javascript has several libraries to test front-end code. But in website testing, how can we write automated tests to ensure that our back-end code (be it python or something else) is working with our front-end code (javascript, HTML, and CSS)?

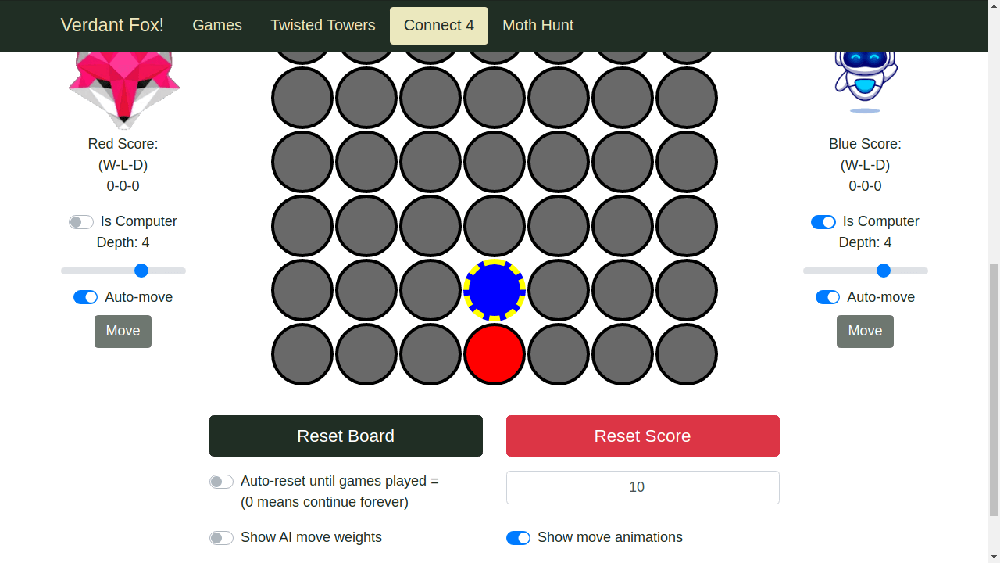

Introducing Playwright, a fast, easy-to-use, and powerful end-to-end browser automation framework. Similar to the Selenium framework, the Playwright framework has tools that allow us to write tests and scripts that act similar to an actual, human website user. And Playwright has API endpoints in javascript, java, .NET, and python! Sound useful? Read on as we use Playwright with python and pytest to write scripts and end-to-end tests for our Connect 4 game web page.

Getting started (installation)

For this blog post, we are going to be using the python Playwright API. We'll install Playwright with pip and we'll interact with and write tests for Playwright in python. I wrote the Playwright code for this blog post with python 3.10, but I believe the tests will work in any python version as low as 3.8. Whatever Python version you are using, I recommend installing Playwright in a virtual environment. Once your virtual environment is activated, to install Playwright and the pytest-playwright-visual plugin which aids in comparing Playwright snapshots, just run these 4 commands:

# Upgrade to the latest pip

pip install --upgrade pip

# Installs the `playwright` package and its `pytest` plugin

pip install playwright

# This step downloads and installs browser binaries for Chromium, Firefox, and WebKit

playwright install

# Installs a 3rd party pytest plugin for saving and comparing Playwright screenshots

pip install pytest-playwright-visual

Auto-generating Playwright code

One cool feature of Playwright is the command playwright codegen URL where URL is the URL you want to start generating Playwright commands from. Let's try it out with my VerdantFox Connect 4 game. Assuming you've completed the above installation steps, run the following command:

playwright codegen https://verdantfox.com/games/connect-4

This opens up 2 windows. The first is a chromium incognito browser at https://verdantfox.com/games/connect-4. This window is connected to the second window which has a couple of buttons at the top and a notepad-like display with python code. The code is a python script for opening this web page with Playwright and then closing the web page and browser. It looks like this:

from playwright.sync_api import Playwright, sync_playwright, expect

def run(playwright: Playwright) -> None:

browser = playwright.chromium.launch(headless=False)

context = browser.new_context()

# Open new page

page = context.new_page()

# Go to https://verdantfox.com/games/connect-4

page.goto("https://verdantfox.com/games/connect-4")

# ---------------------

context.close()

browser.close()

with sync_playwright() as playwright:

run(playwright)

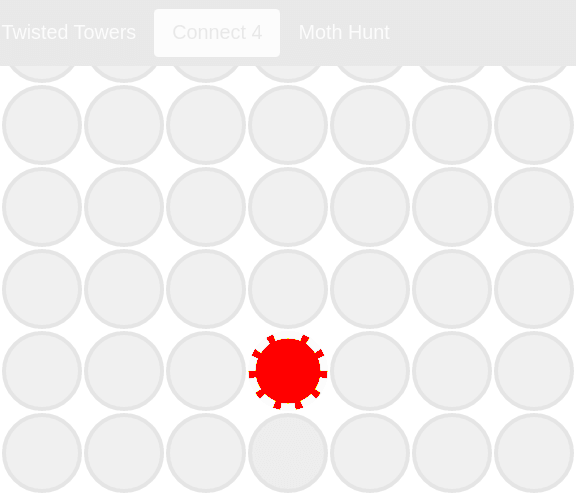

As we interact with the first window opened to our website, the second window will record the corresponding Playwright python code to automate the replication of those website interactions. Let's test this out. Click the bottom-middle circle on the Connect 4 game board. We see the 🔴 red chip fall, followed by the 🔵 blue chip in the same column as normal. In the second window, the following code was added after page.goto("https://verdantfox.com/games/connect-4"):

# Click #circle-3-5

page.locator("#circle-3-5").click()

The end product looks like this:

from playwright.sync_api import Playwright, sync_playwright, expect

def run(playwright: Playwright) -> None:

browser = playwright.chromium.launch(headless=False)

context = browser.new_context()

# Open new page

page = context.new_page()

# Go to https://verdantfox.com/games/connect-4

page.goto("https://verdantfox.com/games/connect-4")

# Click #circle-3-5

page.locator("#circle-3-5").click()

# ---------------------

context.close()

browser.close()

with sync_playwright() as playwright:

run(playwright)

Now, let's copy the code from the second window and paste it into a python file (perhaps called my_playwright.py). If we run the resulting python file as a script with python my_playwright.py, we see a browser window open and then close pretty fast. It did the same things we did to generate the script, but it did them very fast and then closed. To slow the script down so we can see the mouse-click and the resulting falling 🔴 red and 🔵 blue chips, we can pass in one extra argument to the line that says browser = playwright.chromium.launch(headless=False). Let's change this line to the following:

browser = playwright.chromium.launch(headless=False, slow_mo=1000)

This extra argument, slow_mo=1000, tells the Playwright runner to wait 1000 milliseconds (1 second) in between each action. Now if we re-run the script, we'll see the browser open and then we'll see the falling 🔴 red and 🔵 blue chips before the browser closes.

This is awesome! Now we have a means to quickly write Playwright scripts that can automate actions for us. Such scripts could be useful on their own. For instance, we could write a script that runs once an hour that opens up a website, logs in, and polls the page for information. But beyond that, we have a means of quickly finding Playwright commands for writing automated tests, without having to dig through documentation and without having to read through the webpage's DOM (Document Object Model) ourselves.

Understanding the pieces

Now that we have seen how to quickly generate a Playwright script with the playwright codegen command, let's dig a little deeper into that code that was auto-generated to better understand its parts, along with a couple of other parts not included in that auto-generated script.

Browser

The browser object handles the browser that is opened to run Playwright commands. The documentation for the browser object can be found here. Playwright can open a browser for Chromium (the base for browsers like chrome, edge, and brave), WebKit (the base of iOS browser for applications like Safari), or Firefox. When writing a script, we would launch a browser with something like:

browser = playwright.firefox.launch()

There are a few arguments that can be passed to browser.launch() that help define the experience of working with the browser. The most important two to learn are headless and slow_mo.

headless

playwright.chromium.launch(headless=False)

By default headless is set to True. This means that the browser is launched in headless mode. In headless mode, the browser doesn't open visibly but behind the scenes. Oftentimes this is good. For instance, when running tests in CI there will be no screen to look at, so not visibly showing the browser makes sense and is faster. However, when we are developing Playwright scripts or tests, generally we want to see what the script or test is doing. In this case, we will pass headless=False to the browser.launch() code.

slow_mo

playwright.webkit.launch(headless=False, slow_mo=1000)

We mentioned this one briefly above when talking about playwright codegen. By default, actions in a Playwright script or test will proceed one after the other without pause. This means Playwright can run said scripts/tests quite fast -- sometimes too fast to see what is happening. While developing, you might want to slow things down so you can see the actions being performed. To do so pass the slow_mo=MILLISECONDS argument to browser.launch(). Then all subsequent actions called against elements of the webpage will have a delay of MILLISECONDS between each action (e.g. browser.launch(slow_mo=500 will have a 0.5-second delay between each action). Coupling this with headless=False means we can easily follow what the script/test is doing.

Context

A browser's context provides a way to operate multiple independent browser sessions. A new context can be thought of as an "incognito" window. Each new context shares no session, cookies, history, etc. with any other browser context objects. In a script, we call browser.new_context() to generate the new incognito window. Getting a new browser and browser context would look like this:

browser = playwright.chromium.launch(headless=False)

context = browser.new_context()

The full documentation for the browser context can be found here.

Page

The page object provides methods to interact with a single tab in a browser. It is spawned from a browser context with context.new_page(). A browser can have multiple context objects and a context can have multiple page objects. Here are some important methods that we can call from a page object. A full list of interactions can be found here.

page.goto(url, **kwargs)

We can use page.goto(URL) to open a new browser tab at the provided URL. In our example from earlier, page.goto("https://verdantfox.com/games/connect-4") opened a tab to the VerdantFox Connect 4 game web page.

page.screenshot()

page.screenshot() takes a screenshot of the visible page.

page element interactions

Many interactions can be called from a page object. For instance, we can call page.click(selector) to mouse-click an object identified by a selector (more on selectors later). Other page object interactions include page.check(selector) to check a checkbox or radio button, page.hover(selector) to hover over an object, and many others.

page.locator(selector)

The page.locator(selector) method returns an element locator, identified by a selector that can be used to perform actions on the page. More on locators and selectors next. I tend to prefer performing actions on these locators rather than on the page object directly.

Locators

According to the locator's documentation:

Locators are the central piece of Playwright's auto-waiting and retry-ability. In a nutshell, locators represent a way to find element(s) on the page at any moment. A

locatorcan be created with thepage.locator(selector, **kwargs)method.

Locators represent a wrapper on DOM elements found on the page by a selector string (explained next). Locators have a plethora of interactive methods that can be called from them, mirrored by the page element interaction methods. Methods include locator.click() to mouse-click the located element on the page, locator.check() to check a checkbox or radio button, or locator.fill(value) to fill an <input> or <textarea> element. There's even locator.screenshot() to take a screenshot of a specific element on the page.

Locators have a variety of is_something() methods that return a boolean. For instance, locator.is_checked() returns True if the represented element is a checkbox that is checked, locator.is_hidden() returns True if the represented element is hidden on the page, and locator.is_disabled() returns True if the represented object is disabled. A full list of locator methods can be found in the locator's documentation.

A given locator can represent one or more elements. A locator represents multiple elements if its selector applies to multiple elements. You can call locator.count() to get a count of how many elements the locator applies to. In a case where a locator applies to multiple elements, a call like locator.click() would raise an error, since a locator.click() call must apply to only one element. There are methods to get one element out of the many elements represented by the locator. locator.first gets the first element represented by the locator, locator.last gets the last element represented by the locator, and locator.nth(index) gets the nth element represented by the locator where the index passed is 0 based (so locator.nth(0) gets the first element).

Locators can be chained off of one another to narrow down to a more specific locator with locator.locator(selector). For instance, you could call page.locator("#introduction").locator("ul").locator("li").nth(3). This would first get the element with the "introduction" id, then grab the "ul" (unordered list) child element of the "introduction" element, then the "li" (list item) elements of the list, and finally grab the 4th (0, 1, 2, 3) "li" element in the list.

Selectors

Selectors are strings that are used to create locators. There are a variety of selector types that are described in the selector's quick guide documentation. These include text selectors like page.locator("text=Log in").click(), CSS selectors like page.locator("button").click() and page.locator("#nav-bar .contact-us-item").click(), and a variety of other selectors and combinations thereof.

Expect

Asserting on the expected state of an element in a web application can be tricky to time. Assert too early and the expected state might not have been reached yet due to some javascript delay. Wait too long and you're just wasting time. The expect object has methods for creating assertions that retry until the expected condition is met -- or until a timeout is reached. Here's an example from the documentation on Playwright assertions:

from playwright.sync_api import Page, expect

def test_status_becomes_submitted(page: Page) -> None:

# ..

page.click("#submit-button")

expect(page.locator(".status")).to_have_text("Submitted")

Playwright will be re-testing the node with the selector ".status" until the fetched Node has the "Submitted" text. It will be re-fetching the node and checking it over and over, until the condition is met or until the timeout is reached. You can pass this timeout as an option.

There are tons of assertion methods that can be called on an expect object including expect(locator).to_have_text(expected, **kwargs), expect(locator).to_have_css(name, value, **kwargs), expect(locator).to_have_class(expected, **kwargs) and a variety of others including the inverses of all of these (e.g. expect(locator).not_to_have_text(expected, **kwargs)). A full list of expect methods can be found in the documentation.

Playwright and pytest

Cool, we've got a Playwright script and we understand some of the basic building blocks of Playwright. How can we take what we've learned creating such a script, and convert it into automated tests for our website? Introducing the pytest-playwright plugin. Here we'll discuss pytest-playwright CLI flags, Playwright fixtures, and the pytest-playwright-visual plugin, all in the context of a working test I wrote against the VerdantFox Connect 4 game. The test mirrors the simple code we generated earlier with playwright codegen above. We'll call the test file test_connect_4 for future CLI discussions. Here is the file with our one test:

test_connect_4

import re

from typing import Callable

from playwright.sync_api import Locator, Page, expect

def test_single_move(page: Page, assert_snapshot: Callable) -> None:

"""Test that a single move by a human, followed by an AI behaves as expected"""

page.goto("https://verdantfox.com/games/connect-4")

page.locator("#circle-3-5").click()

expect(page.locator("#circle-3-5")).to_have_class(re.compile(r"color-red"))

expect(page.locator("#circle-3-5")).to_have_css(

"background-color", "rgb(255, 0, 0)"

)

expect(page.locator("#circle-3-4")).to_have_class(re.compile(r"color-blue"))

expect(page.locator("#circle-3-4")).to_have_css(

"background-color", "rgb(0, 0, 255)"

)

assert_snapshot(page.locator("#board").screenshot())

Useful CLI flags

Before we dive into the contents of the above test, let's talk about useful CLI flags you can use when running pytests with the pytest-playwright plugin. A full list of pytest-playwright CLI arguments can be found here.

--browser=BROWSER

As we'll soon see in our discussion of fixtures, with Playwright pytests we usually don't work directly with the browser object. As such, we won't use playwright.chromium, playwright.webkit or playwright.firefox to create a browser object. pytest-playwright does this in the background. The pytest-playwright plugin appears to default to running tests against the playwright.chromium browser. To actively choose a browser to run all tests against, you could run pytest test_connect_4 --browser=firefox or --browser=webkit or --browser=chromium. You can even pass multiple flags to run against multiple browsers. For instance, pytest test_connect_4 --browser=firefox --browser=webkit --browser=chromium will run the test test_single_move 3 times back-to-back, one with each browser.

--headed and --slowmo=MILLISECONDS

Because we don't usually work with the browser in tests, we do not call browser.launch(). If you recall from the earlier section on the browser object, the .launch() method takes some useful arguments: headless=BOOL which allows us to run in "headed" mode to watch our tests run, and slow_mo=MILLISECONDS to add a waiting period between each command. To provide this functionality with pytests, we can pass the --headed flag which runs all Playwright tests in "headed" mode (as opposed to "headless" mode), and we can pass --slowmo=MILLISECONDS to add a waiting period of MILLISECONDS milliseconds between each Playwright command.

--screenshot=WHEN and --video=WHEN

When a Playwright test fails, the easiest way to learn why it failed is to visually see what the browser state looks like at the time of the test failure. pytest-playwright is capable of capturing a screenshot at the end of a test with --screenshot=WHEN where WHEN can be on, off, or only-on-failure. It defaults to off, but changing to --screenshot=only-on-failure is a nice way to get an image of the browser at the time of failure for failed tests. This can be especially useful for long-running test suites. If a test suite runs for 10 minutes, and 1 test fails in the middle, having that snapshot to look at afterward can save a headache.

Here's an example of running the above test with --screenshot=on:

What's even better than a screenshot? A video (sometimes). With --video=WHEN pytest-playwright can capture a video of the browser during each test. WHEN can be set to off (default, fastest), on (capture a video of each test), and retain-on-failure (capture a video for each test, but delete the video if the test passes). If you use this flag, I suggest the retain-on-failure version.

Here's an example of running the above test with --video=on (converted to a GIF for this blog post):

Useful fixtures

With pytests, we can make fixtures perform much of the boilerplate set up code needed when using Playwright. Recall from our codegen auto-generated script, we had the following setup code:

browser = playwright.chromium.launch(headless=False)

context = browser.new_context()

page = context.new_page()

With pytest, all of this boilerplate can be replaced by the page fixture for efficient browser, context, and page management behind the scenes. The result looks like this:

def test_basic(page):

"""A basic test"""

...

Much leaner. But the browser and context can be accessed when needed with their own fixtures. The following is a list of the most important fixtures you might use while writing Playwright pytests. A full list of pytest-playwright fixtures can be found here.

browser

The browser fixture is a session scoped fixture, meaning a browser is generated at the start of all Playwright tests, and it is closed after the last test completes. Generating the browser only once means subsequent tests run faster by sharing that resource. This fixture returns a browser instance. Recall, the useful CLI flags section above for how to set the browser type, headed mode, and slow_mo.

context

The context fixture is a function scoped fixture, meaning a new browser context is generated off of the session scoped browser for each test, and it is closed after that test finishes. This is important because it means each test is isolated from one another in a separate "incognito" window with a separate session, separate cookies, etc. The context fixture returns a browser.context instance.

page

The page fixture is a function scoped fixture and it is called off the function scoped context fixture generating a new page object in a new browser context for each test. The page fixture returns a browser.context.page instance. The page fixture is the most commonly used fixture when writing tests since it provides the most useful functionality while abstracting away the browser and context which are not usually necessary when writing tests.

is_chromium, is_webkit, and is_firefox

The session-scoped fixtures is_chromium, is_webkit, and is_firefox all simply return a boolean that is True if the underlying browser used for the test is that type. They can be useful if your test needs to behave differently for different browsers.

assert_snapshot

The assert_snapshot fixture is only available if the pytest-playwright-visual pytest plugin is pip installed. The fixture returns a function that can assist with comparing Playwright screenshots. Recall, Playwright can take screenshots of the browser at any given time with page.screenshot() or locator.screenshot(). This fixture and returned function of the same name allows for easy comparison of screenshots between test runs. Here's how it works.

The first time you run your test that has the code assert_snapshot(page.screenshot()), the test will fail with the message "Failed: --> New snapshot(s) created. Please review images". The code saves a screenshot to a folder in the test's directory with a name related to the test, browser, and OS. You can inspect this image to see if it looks right. If it is right, this image becomes the gold standard for what the browser window should look like when it hits that line of code. The next time you run the test, when the test reaches the line assert_snapshot(page.screenshot()), the assert_snapshot function will compare your saved screenshot from last time with a new screenshot generated from this run. If the two images are the same, that line of code passes. If they are different, the test fails.

On failure, a new set of images are stored in a folder named snapshot_tests_failures. There is one image prefixed with Actual_ that is an image from this test run. There is one image prefixed with Expected_ that is a copy of your stored "gold standard" image. And there is one image prefixed with Diff_ which nicely dulls/whitens most of the image to highlight just the pixels that were different. The Diff_ image can be very useful in determining what changed between runs.

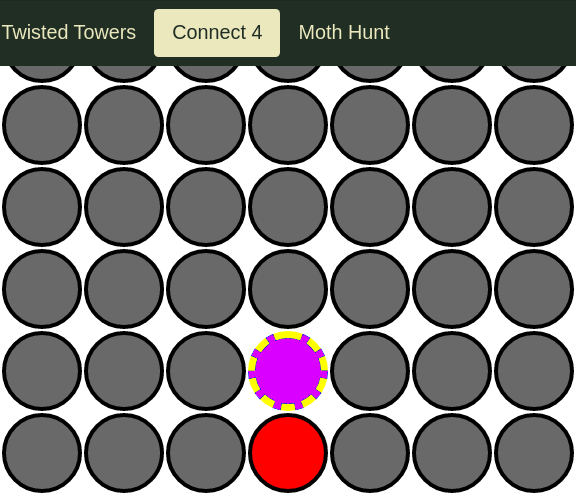

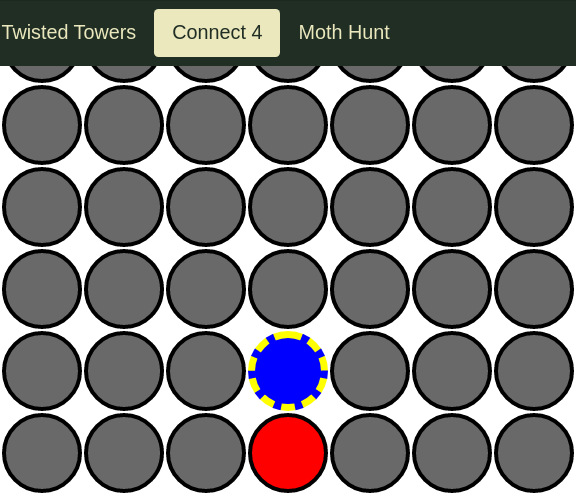

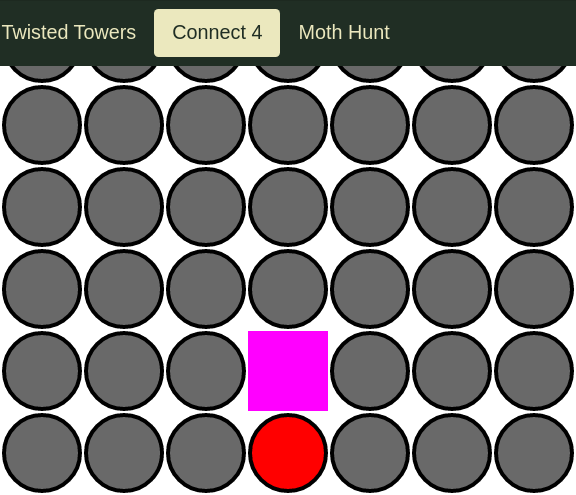

Here are examples of "actual", "expected", and "diff" images I generated by altering the color of one circle of the "expected" image and then re-running the test, resulting in a failed image comparison.

"Expected" image (generated from the first test run, altered with a "paint"-like program):

"Actual" image (generated from the second run that failed on image comparison):

"Diff" image comparing the changed pixels between the "expected" and "actual" images:

Here's a problem that might come up: how can we effectively compare images where part of the image is expected to change between test runs? An example might be a web page with a constantly updating clock. In this case, the easiest way to make the images consistent between runs is to pass the argument mask=LOCATORS to the screenshot() method where LOCATORS is a list of locator objects. This "masks" the located elements by replacing them with purple rectangles. Here's an example where I update my test's snapshot assert_snapshot(page.locator("#board").screenshot()) with the code assert_snapshot(page.locator("#board").screenshot(mask=[page.locator("#circle-3-4")])).

Putting it all together

Recall, that this is the example test I wrote.

import re

from typing import Callable

from playwright.sync_api import Locator, Page, expect

def test_single_move(page: Page, assert_snapshot: Callable) -> None:

"""Test that a single move by human, followed by AI behaves as expected"""

page.goto("https://verdantfox.com/games/connect-4")

page.locator("#circle-3-5").click()

expect(page.locator("#circle-3-5")).to_have_class(re.compile(r"color-red"))

expect(page.locator("#circle-3-5")).to_have_css(

"background-color", "rgb(255, 0, 0)"

)

expect(page.locator("#circle-3-4")).to_have_class(re.compile(r"color-blue"))

expect(page.locator("#circle-3-4")).to_have_css(

"background-color", "rgb(0, 0, 255)"

)

assert_snapshot(page.locator("#board").screenshot())

Let's step through this test to summarize what we've learned about Playwright elements in the context of pytest.

def test_single_move(page: Page, assert_snapshot: Callable) -> None:

When we define the test we use the page and assert_snapshot fixtures by providing them by name as parameters to the test.

page.goto("https://verdantfox.com/games/connect-4")

We call the page.goto(URL) method to send the browser to the URL https://verdantfox.com/games/connect-4.

page.locator("#circle-3-5").click()

We create a locator object for the element with the id circle-3-5 (corresponding to a circle on the game board). We call the .click() method on this locator object to mouse-click that circle element.

expect(page.locator("#circle-3-5")).to_have_class(re.compile(r"color-red"))

expect(page.locator("#circle-3-5")).to_have_css(

"background-color", "rgb(255, 0, 0)"

)

expect(page.locator("#circle-3-4")).to_have_class(re.compile(r"color-blue"))

expect(page.locator("#circle-3-4")).to_have_css(

"background-color", "rgb(0, 0, 255)"

)

When we clicked the circle, we expect this to cause one 🔴 red chip to fall followed by one 🔵 blue chip in the same column as the circle that was clicked. We confirm this by creating an expect object from a locator object corresponding to the circle we expect to eventually have a 🔴 red chip. By inspecting this circle with chrome's "inspect" tool, we can determine that this 🔴 red chip is represented by a CSS class "color-red" which causes a CSS background color of "red" or "rgb(255, 0, 0)".

So first, we call the expect object's to_have_class() method, passing in the "color-red" class in the form of a regular expression. Then, on the next line, we call the to_have_css() method on an identical expect object, passing in the CSS property "background-color" and the expected value of the background-color, "rgb(255, 0, 0)". Then we repeat these expectations for the 🔵 blue chip circle just above the 🔴 red chip circle. Here we expect the circle to have the CSS class "color-blue" and the background color "blue" or "rgb(0, 0, 255)", so we substitute those values where appropriate for the corresponding values from our 🔴 red chip circle expect calls.

assert_snapshot(page.locator("#board").screenshot())

Finally, we take a screenshot of the element with the board id, corresponding to the game board, enclosing that screenshot with the assert_snapshot() function/fixture. Thus screenshots from subsequent test runs are compared and must match the first run's screenshot.

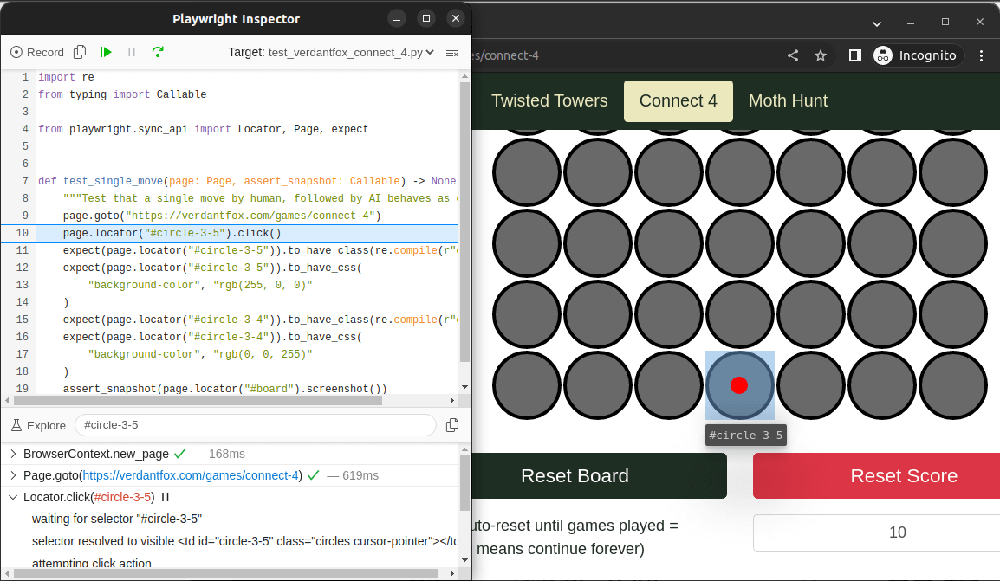

Playwright debugger tool

One very useful tool that comes with Playwright is the Playwright debugger (also known as the Playwright Inspector). To use the debugger, set the PWDEBUG environment variable to 1. This tool can be used for both Playwright scripts and pytests.

PWDEBUG=1 pytest test_connect_4

The debugger forces the test or script into "headed" mode. When the above command runs, two windows pop up. One is a browser. The other is the Playwright inspector debugger tool.

The test or script starts paused, the browser empty. The Playwright debugger tool highlights the next line of code to run. There is a "Resume" button in the debugger to play the test like normal in "headed" mode. There is also a "Step over" button. Pressing the "Step over" button runs just the highlighted line of code. As you run the code, with each subsequent press of the "Step over" button, the highlighted code is run and the next line of code is highlighted in turn. When a line of code is highlighted, the "browser" window indicates what action or expect assertion will be performed next by highlighting that area, showing its identifier below it, and showing a red dot where the mouse is hovering. This can be quite handy for making sense of what each line of code is doing in your test or script as it is being run.

Conclusions

That rounds out all you need to know to write successful Playwright scripts and tests. Of course, there are many concepts and features not covered by this blog post, and I highly encourage you to explore the Playwright documentation for yourself. My take on this framework is that it can be super useful for end-to-end testing. It is especially useful in testing highly interactive web pages with lots of javascript on the front end. The framework creates fast tests, and it is higher-level and more intuitive than the Selenium framework that fulfills the same use case. The documentation is amazing and makes it so easy to quickly learn the framework at a deep level. I'll be using Playwright for automated end-to-end testing of this website. I recommend you do the same for your own end-to-end and visual testing needs.

Verdant Fox

Verdant Fox